What is it?

The protégé effect is a concept in learning that suggests we learn more effectively by teaching others, and it doesn’t necessarily mean that these “others” are less knowledgeable.

This idea isn’t new. Two thousand years ago, the famous Stoic philosopher Seneca wrote: “Docendo discimus,” which means “We learn by teaching.”

I like the quote attributed to writer Robert Heinlein even more: “When one teaches, two learn.”

Why does it work?

In short, when we explain material to others, certain mechanisms engage that are absent when we passively absorb information.

- Before explaining to others, we first need to structure and organize the information in our heads.

- By teaching, we become responsible not only for our own knowledge but also for the knowledge of the person who listens to or reads us. This also motivates us to study the material in more detail.

- It activates the mechanism of metacognition. In other words, we start to become aware of our own knowledge gaps, prompting us to fill them and improve our understanding.

My Personal Experience

From my experience, I’ve always found that this approach works.

The first example I can recall goes back to my school days, when our history teacher, Andrii Oleksiiovych (who now serves in the military to defend the country), assigned us to prepare a presentation on the Crimean War. So much time has passed since that lesson, yet I still remember interesting facts, particularly that the allied forces had a significant advantage on the battlefield thanks to rifled barrels compared to smoothbores.

Since then, I’ve had opportunities to make presentations on various topics and deliver lectures, and each time, I discovered that, first, this knowledge is deeper and more structured than what you typically get from reading, listening, or watching material. And second, this knowledge stays with you much longer.

Recently, I started this blog and have written two articles so far. Besides the warm feeling that they might be useful to someone, I also realized that preparing articles motivates me to delve deeper into the topic I chose.

Scientific Basis

But this was my personal experience, and I’m curious about how much it is supported by research.

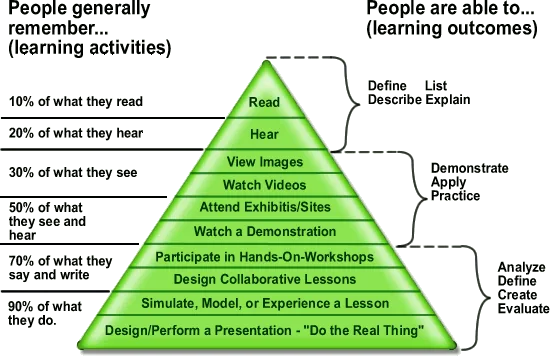

The first thing I found—and recognized immediately, probably from seeing it on LinkedIn—is the learning pyramid.

| Retention Rate | Learning Activity Before Knowledge Test |

|---|---|

| 90% | Teach someone else/use it immediately. |

| 75% | Practice what you learned. |

| 50% | Participate in a group discussion. |

| 30% | Watch a demonstration. |

| 20% | Watch audiovisual material. |

| 10% | Read. |

| 5% | Listen to a lecture. |

This concept looks quite convincing, even shocking. If we believe it, attending a university lecture is 18 times less effective than teaching someone else.

Usually, if you see shocking numbers, it’s a marker that this information may be unreliable. And indeed, as it turns out, this pyramid has no scientific basis. You can read more about it here.

So is the protégé effect just a myth? Not exactly. This article presents studies that confirm teaching others can improve your own understanding of the material. Specifically:

- A 1984 study showed that the expectation of teaching others boosts intrinsic motivation more than merely preparing for a test.

- A 2009 study on “teachable agents” (digital characters capable of reasoning based on acquired knowledge) found that students who interacted with these agents showed significant improvement in learning compared to those who did not. In other words, even simulated teaching can activate the protégé effect.

- A 2014 study confirms that the “expectation of teaching others” enhances “learning effectiveness at home and in the classroom.”

- A 2016 study demonstrated that learners preparing to teach used 1.3 times more metacognitive strategies than those who didn’t.

- Another 2016 study found that the expectation of teaching others motor skills improved those skills.

Interesting Ways to Use the Protégé Effect

There are fairly obvious (but effective) ways to use the protégé effect, such as:

- Creating videos or podcasts

- Writing articles

- Answering questions on forums

- Mentoring

There are also less obvious ways:

Teach a Family Member or Friend

If you’re learning a new technology, programming language, or anything else, try teaching someone close to you. If they have no understanding of the subject, it’s even more fun. You’ll have to use simple terms, accessible metaphors, and examples. Once, my friend, a chemist, explained the colloidal level in chemistry to me through an analogy with a bus stop. I only remember the name of this level, but it was quite interesting back then!

The Duckling Method

One of the most interesting methods is the duckling method. This method involves placing (or imagining) a toy duck on your desk and, when you have a difficult question, asking the toy as if it could respond. As is known, properly formulating a question provides half the answer.

It reminds me of how my friend Zhenia, when he has questions about programming topics I know better, asks me something but finds the answer himself before I can respond. In this context, he’s using the duckling method, and I’m… quack-quack.

You can use this idea not only when you have questions but also when you want to deepen your understanding of a topic. No one to teach? Teach a duck!

Using AI

We’re all used to using AI as a teacher, but what if we used it as a student? The author of this article suggested that ChatGPT take on the role of an inquisitive Spanish student who wanted to hear what the author had learned.

Conclusion

That’s all. Remember, teaching others is not only beneficial for them but also for you.